|

Posted June 1, 2010

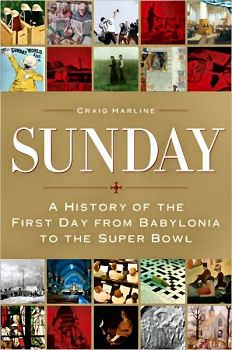

Book: Sunday: A History of the First Day from Babylonia to the Super Bowl Author: Craig Harline Doubleday. NY. 2007. Pp. 450 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

An Excerpt from the Book If European immigrants of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, or Latinos of the 1950s, found integration into established American congregations difficult, then the overwhelming majority of black Americans found it nearly as impossible as ever. Present in significant numbers since the eighteenth century, blacks in America remained far more numerous than Latinos, totaling 18.9 million by 1960, some 64 percent of them were Baptist and 23 percent Methodist or African Methodist Episcopal, with a smaller number who were Catholic. Despite efforts of some churches to integrate American congregations during the 1950s, 95 percent of blacks continued to worship separately on Sunday — just as they did much else separately both before and after the Civil War. Partly because of this, Sunday always had great meaning among black Americans as a day of refuge. Indeed, William McClain has recently written that although Sunday was an organizing point for many people, it had been especially so for the black church and community. “People talk about losing the Lord’s Day, well black people never lost it!” Sunday was long the moment when black Americans found “hope and sanctity and blessing from a week of loss and indignities.” It was a day not only of the usual rejuvenation, high-heeled shoes, pressed dresses, and suits and ties found among many groups, but especially “a testimony of God’s ability to sustain life in the midst of trail.” Sunday always came, Sunday always endured. Although McClain did not mention the French and Russian attempts to eliminate Sunday, their failures wold have confirmed his sense of Sunday as a symbol of endurance. Table of Contents: 1. Prologue: Sunday ascendant 2. Sunday middle-aged 3. Sunday reformed 4. Sunday al la mode 5. Sunday obscured 6. Sunday still 7. Sunday all mixed up |

|