|

Posted January 27, 2005

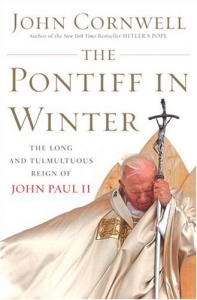

Book: The Pontiff in Winter: Triumph and Conflict in the Reign of John Paul II Author: John Cornwell Doubleday, New York, pp. 336 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

For more than a quarter of a century, John Paul II has firmly set his stamp on the billion-member-strong Catholic Church for future generations, and he has become one of the most influential political figures in the world. His key role in the downfall of communism in Europe, as well as his apologies for the Catholic Church’s treatment of Jews and to victims of the Inquisition, racism, and religious wars, won him worldwide admiration. Yet his papacy has also been marked by what many perceive as misogyny, homophobia, and ecclesiastical tyranny. Some critics suggest that his perpetuation contributed to the Church’s traditional hierarchical paternalism contributed to pedophiliac behavior in the priesthood and encouraged superiors to sweep the crimes under the carpet. The Pontiff in Winter brings John Paul’s complex, contradictory character into sharp focus. In a bold, highly original work, John Cornwell argues that John Paul’s mystical view of history and conviction that his mission has been divinely established are central to understanding his pontificate. Focusing on the period from the eve of the millennium to the present, Cornwell shows how John Paul’s increasing sense of providential rightness profoundly influenced his reactions to turbulence in the secular world and within the Church, including the 9/11 attacks, the pedophilia scandals in the United States, the clash between Islam and Christianity, the ongoing debates over the Church’s politics regarding women, homosexuals, abortion, AIDS, and other social issues, and much more. An Excerpt from the Book: John Paul will go down in history as the Pope who helped the Polish people oust Communist rule; who helped prompt the process that brought down communism and ended the Cold War, thus making the world a safer place. Of all world figures in the last quarter century, moreover, he stands out as a man of peace. On his deeply emotional final visit to Lourdes in August 2004, he wept at the grotto of the Virgin and prayed for peace. “Join me,” he asked the faithful, “in imploring the Virgin Mary to obtain for our world the longed-for gift of peace. May forgiveness and brotherly love take root in human hearts. May every weapon be laid down and all hatred and violence put aside. May everyone see in his neighbor not an enemy to be fought but a brother to be accepted and loved, so that we may join in building a better world.” But what will be his lasting legacy for the Catholic Church? How will his influence be felt among the billion-strong faithful in years to come? And what sort of pope ideally should follow him, immediately or eventually? Throughout the worldwide Church one finds everywhere vibrant Catholic communities: people working, and dying, for the faith; selfless ministers, sisters, and laity working for the sick and the poor; members of the faithful making the world a better place. The spirit of Vatican II is at work and cannot be quenched. But there are countless millions of Catholics who have fallen away because they have become demoralized and excluded under John Paul II. His major and abiding legacy, I believe, is to be seen and felt in various forms of oppression and exclusion, trust in papal absolutism, and antagonistic divisions. Never have Catholics been so divided; never has there been so much contempt and aggression between Catholics. Never has the local Church suffered so much at the hands of the Vatican and papal center. John Paul has exhibited from time to time a rhetorical appreciation of the dual role of the two great impulses within the Church in the world, the universal and the local, that should beat in mutual empowerment and understanding, not in competition or rivalry. In the interests of unity, and faced with what he saw as the centrifugal fragmentation of the Church in the postconciliar era, John Paul emphasized the institution of the universal at the expense of the local. To achieve this end, he wielded the instruments of power available to him —the Petrine office and the outreach of the Curia — binding the local Church more closely to the papacy. And he traveled, treating every nation, diocese, and parish as his own. John Paul had neither doubts or scruples in this vaulting hubris, because he was convinced that he had divinely ordained mystical endorsement; there were no coincidences — it was all meant from the beginning, foretold, predestined. Table of Contents: 1. Close encounters 2. Two:stagestruck 3. The Eternal City 4. Professor and pastor 5. Bishop and cardinal 6. Combating Communism 7. Signs of Contradiction 8. “Be Not Afraid!” 9. The universal pastor 10. Assassination and Fatima 11. Back on the road 12. Poland and the fall of Communism 13. John Paul, saints and scientists 14. John Paul’s conflict with democracy 15. Pluralism and the Pope 16. Women 17. Sexology and life 18. Millennium fever 19. Ufficioso and Ufficiale 20. The patient Pope 21. To the Holy Land 22. Third secret of Fatima 23. Jubilee theatricals 24. Contrition and the Jews 25. Are you saved? 26. Who runs the Church? 27. 9/11 28. The sexual abuse scandal 29. John Paul and AIDS 30. Founding fathers 31. John Paul and the Iraq War 32. John Paul’s decline 33. Mel Gibson’s The Passion 34. George W. Bush and John Paul 35. John Paul’s grand design Epilogue: The legacy of John Paul II |

|