|

Posted April 4, 2006

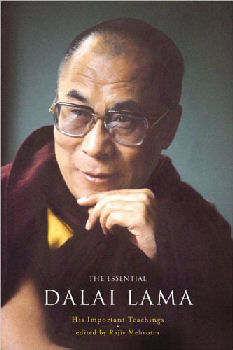

Book: The Essential Dalai Lama: His Important Teachings Edited by Rajiv Mehrotra Pilgrim Books, London, England, New York, 2005, pp. 274 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

Covering topics such as the quest for human happiness, foundations of Buddhism, Karma, focusing the mind, ethics and society, the Buddhist perspective on the teachings of Jesus, and much more. The Essential Dalai Lama will be the perfect compilation for anyone who wishes to have one source for the Dalai Lama’s teachings or who seeks an introduction to the philosophy and practice of Buddhism. An Excerpt from the Book: Buddhist Perspectives on the Teachings of Jesus Since this dialogue has been organized by the World Community for Christian Meditation and the main audience attending here is practicing Christians who have a serious commitment to their own practice and faith, my presentation will be aimed primarily toward that audience. Consequently, I shall try to explain those Buddhist techniques or methods that can be adopted by a Christian practitioner without attaching the deeper Buddhist philosophy. Some of these deeper, metaphysical differences between the two traditions may come up in the panel discussion. My main concern is this: How can I help or serve the Christian practitioner? The last thing I wish to do is to plant seeds of doubt and skepticism in their minds. As mentioned earlier, it is my full conviction that the variety of religious traditions today is valuable and relevant. According to my own experience, all of the world’s major religious traditions provide a common language and mesage upon which we can build a genuine understanding. In general, I am in favor of people continuing to follow the religion of their own culture and inheritance. Of course, individuals have every right to change if they find that a new religion is more effective or suitable for their spiritual needs. But, generally speaking, it is better to experience the value of one’s own religious tradition. Here is an example of the sorts of difficulties that may arise in changing one’s religion. In one Tibetan family in the 1960s, the father of the family passed away, and the mother later came to see me. She told me that as far as this life is concerned she was Christian, but for the next life there was no alternative for her but Buddhism. How complicated! If you are Christian, it is better to develop spiritually within your religion and be a genuine, good Christian. If you are a Buddhist, be a genuine Buddhist. Not something half-and-half! This may cause only confusion in your mind. Before commenting on the text, I would like to discuss meditation. The Tibetan term for meditation is gom, which connotes the development of a constant familiarity with a particular practice or object. The process of “familiarization” is key because the enhancement or development of mind follows with the growth of familiarity with the chosen object. Consequently, it is only through constant application of the meditative techniques and training of the mind that once can expect to attain inner transformation or discipline within the mind. In the Tibetan tradition there are, generally speaking, two principal types of meditation. One employs a certain degree of analysis and reasoning and is known as contemplative or analytical meditation. The other is more absorptive and focusing and is called single-pointed or placement meditation. Let us take the example of meditating on love and compassion in the Christian context. In an analytical aspect of that meditation, we would be thinking along specific lines, such as the following: to truly love God one must demonstrate that love through the action of loving fellow human beings in a genuine way, loving one’s neighbor. One might also reflect upon the life and example of Jesus Christ himself, how he conducted his life, how he worked for th benefit of other sentient beings, and how his actions illustrated a compassionate way of life. This type of thought process is the analytical aspect of meditation on compassion. One might meditate in a similar manner on patience and tolerance. These reflections will enable you to develop a deep conviction in the importance and value of compassion and tolerance. Once you arrive at that certain point where you feel totally convinced of the preciousness of and need for compassion and tolerance, you will experience a sense of being touched, a sense of being transformed from within. At this point, you should place your mind single-pointedly in that conviction, without applying any further analysis. Your mind should rather remain single-pointedly in equipoise; this is the absorptive or placement aspect of meditation on compassion. Thus, both types of meditation are applied in one meditation session. Why are we able, through the application of such meditative techiques, not only to develop but to enhance compassion? This is because compassion is a type of emotion that possesses the potential for development. Generally speaking, we can point to two types of emotion. One is more instinctual and is not based on reason. The other type of emotion – such as compassion or tolerance – is not so instinctual but instead has a sound base or grounding in reason and experience. When you clearly see the various logical grounds for their development and you develop conviction in these benefits, then these emotions will be enhanced. What we see here is a joining of intellect and heart. Compassion represents the emotion, or heart, and the application of analytic meditation applies the intellect. So, when you have arrived at that meditative state where compassion is enhanced, you see a special merging of intellect and heart. If you examine the nature of these meditative states, you will also see that there are different elements within these states. For example, you might be engaged in the analytic process of thinking that we are all creations of the same Creator, and therefore, that we are all truly brothers and sisters. In this case, you are focusing your mind on a particular object. That is, yhour analytic subjectivity is focusing on the idea or concept that you are analyzing. However, once you have arrived at a state of single-pointedness — when you experience that inner transformation, that compassion within you – there is no longer a meditating mind and a meditated object. Instead, your mind is generated in the form of compassion. These are a few preliminary comments on meditation. Now I will read from the Gospel. You have heard that they were told, “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” But what I tell you is this: do not resist those who wrong you. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn and offer him the other also. If anyone wants to sue you and takes your shirt, let him have your cloak as well. If someone in authority presses you into service for one mile, go with him two. Give to anyone who asks, and do not turn your back on anyone who wants to borrow. The practice of tolerance and patience which is being advocated in these passages is extremely similar to the practice of tolerance and patience which is advocated in Buddhism in general. And this is particularly true in Mahayana Buddhism in the the contextg of the bodhisattva ideals in which the individual who faces certain harms is encouraged to respond in a nonviolent and compassionate way. In fact, one could almost say that these passages could be introduced into a Buddhist text, and they would not even be recognized as traditional Christian scriptures. Table of Contents: 1. Words of truth: a prayer The Vision 2. The quest for human happiness 3. Our Global family 4. Compassion 5. Universal responsibility Buddhist Perspectives 6. Introduction 7. Laying the groundwork 8. The Buddha 9. Four noble truths 10. Karma 11. The Bodhisattva ideal 12. Interdependence 13. Dependent origination 14. Awareness of death Practice 15. Creating the perspective for practice 16. Refuge: the three jewels 17. Meditation: a beginning 18. Transforming the mind through meditation 19. Environment/symbols/posture/ breathing 20. The nature of the mind 21. Practice of calm abiding 22. Generating the mind of enlightment 23. Eight verses for training the mind 24. Meditation on emptiness 25. Tantra: deity yoga 26. Relying on a spiritual teacher A World in Harmony 27. Ethics and society 28. Science and spirituality 29. Buddhist concept of nature 30. A wish for harmony (among religions) 31. Buddhist perspectives on the teachings of Jesus The sheltering tree of interdependence |

|