|

Posted February 22, 2010

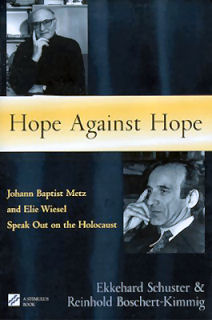

Book: Hope Against Hope Author: Ekkehard Schuster & Reinhold Boschert-Kimmig Paulist Press. New York. 1999. Pp. 106. Introduction

It would take years, even decades, before the one interiorized that horror and grasped it as something that unsettled all of his questions about God and about human beings, and before the other found a literary and religious language with which to tell its story. The Christian theologian and the Jewish writer are bound together by their passion for remembrance. This remembrance is dangerous, but it bears within a saving kernel. Both their biographies and their works are bound together by the memory of human suffering, of history’s victims, as well as by a suffering unto God. Neither puts any store on comfort or consolation; herein lies their importance. Hope is found only in a defiant “and yet.” For, as one of them would put it, true faith is born in the very heart of despair, and as the other would say, human beings do not come to self-knowledge in that which is comforting, but in that which is unsettling. An Excerpt from the Book: You talk about remembrance of the events of the past. What place does it take in your work? Elie Wiesel: I have written many books; perhaps some would say too many. I have written about the Bible and about the Talmud. I have written about Hassidism and Jerusalem. I have written on so many different themes that one morning a few years ago I suddenly began to wonder what all my books have in common. They tell of such diverse times and so many different themes, subjects which are so different from one another. What do they have in common? Their commonality is the obligation to remember. When I talk about the Akedah, the biblical binding of Isaac, or when I recount the story of the founder of Hassidism, the Besht, the master of holiness, of the Good Name, or when I tell stories about Jerusalem or – rarely– about our tragedy, it is the obligation to remember that drives me to take pen in hand and write one word after another. I ask myself what the opposite of memory is. The opposite of memory is the sickness of forgetting, what today we call Alzaheimer’s Disease. That is why I wrote a novel about it. I must tell you that it is one of the saddest stories I have written yet. I thoroughly studied this disease. I have met with its victims and with their families. There is no escape from it. Anger can be creative. Anger can represent the beginning of growth. Alzheimer’s or forgetting is the end. For these reasons my message is a very simple one: Never fight against memory. Even if it is painful, it will help you: it will give you something; it will enrich you. Ultimately, what would culture be without memory? What would philosophy be without memory? What would love for a friend without remembering that love the next day? One cannot live without it. One cannot exist without remembrance. Table of Contents: Johann Baptist Metz Biographical notes The church today: between resignation and hope Theological interruptions Philosophical-theological encounters – formative figures Narrative and memory — aesthetics and ethics The question of time and suffering unto God Elie Wiesel Biographical notes To be a Jew – hope from remembrance Literary and religious teachers Interrupting language: the experience of Auschwitz An ethic drawn from memory Wrestly with God |

|