|

Posted January 7, 2008

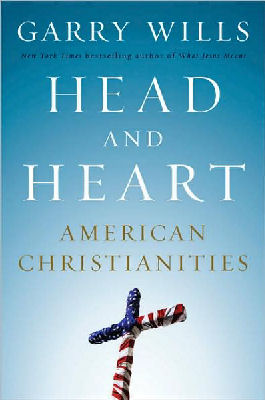

Book: Head and Heart: American Christianities Author: Garry Wills Penguin Press. New York. 2007. Pp. 626 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

A religious revolution occurred in America in the eighteenth century, one that saw the emergence of an Enlightenment religious culture whose hallmarks were tolerance for other faiths and a belief that religion was a matter best divorced from political institutions — the proverbial “separation of church and state.” Wills shows us just how incredibly radical a departure this separation was: there was no precedent for it, in England or anywhere else in the world. To put this great leap in perspective, Garry Wills provides a grounding in the pre-Enlightenment religion that preceded it, beginning with the early Puritans, and charts the intellectual genealogy of the emergence of religious dissent, and the colonies’ efforts to deal with it, both benignly and brutally. He then provides a thrilling clear unpacking of the steps, particularly Madison’s and Jefferson’s by which church-state separation was enshrined in the Constitution, and reveals the great irony of the efforts of today’s Religious Right to blur the lines between the two. In fact, it is precisely that separation that has caused religion in America to flourish so spectacularly. The disestablishment of religion created a free market, as it were, and competition for souls led to the profusion of sects and denominations across the length and breadth of the land. As Garry Wills examines the key movements and personalities that have transformed America’s religious landscape, we see again and again the same pattern emerge: a cooling of popular religious fervor followed by a grassroots explosion in Evangelical activity, and an aggressive reassertion of religious values into the public sphere, generally at a time of great social transformation and anxiety. But such forces inevitably go too far, interfering too much in American public life, causing a backlash, and the cycle begins again. Garry Wills closes with a penetrating dissection of the Religious Right’s current machinations and the threat they pose to the enlightened religion that has proved to be such a fertile and enduring force across almost four hundred years of American history. In the end, Wills’s abiding message is to be vigilant against the triumph of emotions over reason, but to know that the tension between the two is in fact necessary, inevitable, and unending. An Excerpt from the Book: Catholics, who had begun to make a mark on the national scale in the 1930s, prospered after the war. They were becoming assured enough to be self-critical. Their spokespersons looked around in the postwar period and gauged their own shortcomings, as a first step toward overcoming them. An extensive survey done in 1945 found Catholics as a whole less educated than Protestants or Jews. But postwar affluence and the G.I. Bill raised their educational level. Two priests, John Tracey Ellis and Walter Ong, along with the layman Thomas O’Dea, set the agenda for a more rigorous intellectual life in their church. Young men and women were flocking to the seminaries and convents to become priests and nuns. The number of Catholic converts surged. The most famous of these was probably Thomas Merton, whose account of his conversion, The Seven Storey Mountain, was a best-seller in 1948. Fulton Sheen won a number of converts, including Clare Booth Luce, wife of the magazine founder, Henry Ford II, son of the automobile pioneer. Paul Blanshard renewed some old nativist charges against Catholicism in his 1949 book, American Freedom and Catholic Power. But Catholics’ participation in the war effort made it hard to question their American-ness. Catholics held all political offices but the highest one — and that would soon change. There were almost a hundred Catholics in Congress. The previously slow development of intellectual life in the immigrant church changed with the revival of Thomistic studies, which spread beyond Catholics into the program of Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler at the University of Chicago. Thomist scholars from abroad – Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson – were invited in the 1950s to give the prestigious Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. Harvard gave a chair in 1958 to the Catholic historian from England Christopher Dawson. The mystical French paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was being studied already, though his vogue in America would expand in the Sixties. Catholic novelists in America (Flannery O’Cooner and J.F. Powers) and from England (Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh) enjoyed a wide audience. The peak of Catholic prestige and influence came at the end of this postwar period, in two brief reigns as the Sixties began — that of Pope John XXIII (1958-63) and that of President John F. Kennedy (1961-63). The pope addressed two encyclicals to the whole world — Mater et Magistra (1961) and Pacem in Terris (1963) – and the world responded to them. Robert Hutchins ran an international congress devoted to exploring the promise of Pacem in Terris. When the pope opened the Second Vatican Council, Protestant and Jewish observers were welcomed, and the secular press closely followed its proceedings — especially through a learned insider’s accounts sent to the New Yorker. The Council repudiated the old libel that Jews were Christ killers, and finally recognized the validity of pluralist societies — the old position was that governments should recognize a monopoly of “the one true religion.” it was an American John Courtney Murray, whose views were adopted by the universal church. Table of Contents: 1 Puritans 2. Preludes to enlightenment 3. Unitarians 4. Disestablishment 5. Transcendentalism 6. Religion of the heart 7. Doomsday or progress? 8. Reversals 9. Euphoria 10. The Karl Rove Era |

|