|

Posted November 17, 2005

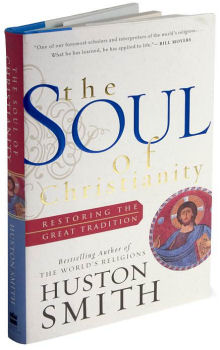

Book: The Soul of Christianity: Restoring the Great Tradition Author: Huston Smith HarperCollins, NY, 2005, pp. 176 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

Thought there is a wide variety of contemporary interpretations of Christianity — some of them conflicting — Smith cuts through these to describe Christianity’s “Great Tradition,” the common faith of the first millennium of believers, which is the trunk of the tree from which Christianity’s many branches, twigs, and leaves have grown. This is not the exclusivist Christianity of strict fundamentalists, nor the liberal, watered-down Christianity practiced by many contemporary churchgoers. In exposing biblical literalism as unworkable as well as enumerating the mistakes of modern secularists, Smith presents the very soul of a real and substantive faith, one still relevant and worth believing in. Smith rails against the hijacked Christianity of politicians who exploit it for their own deeds. He decries the exercise of business that widens the gap between the rich and poor, and fears education has lost its sense of direction. For Smith, the media has becme a business that sensationalizes news rather than broadening our understanding, and art and music have become commercial and shocking rather than enlightening. Smith reserves his harshest condemnation, however, for secular modernity, which has stemmed from the misreading of science — the mistake of assuming that “absence of evidence” of a scientific nature is “evidence of absense.” These mistakes have all but banished faith in transcendence and the Divine from mainstream culture and pushed it to the margin. Though the situation is grave, these modern misapprehensions can be corrected, says Smith, by reexamining the great tradition of Christianity’s first millennium and reaping the lessons it holds for us today. This fresh examination of the Christian worldview, its history, and its major branches provide the deepest, most authentic vision of Christianity — one that is both tolerant and substantial, traditional and relevant. An Excerpt from the Book: The Christian story is the story of how “God became man so man might become God” [Irenaeus]. This “becoming God” happens individually, communally, and cosmically. The first two divinizations are directions rather than destinations — sanctity in the case of individuals, and in the case of the church the degree to which, congregation by congregraton, it brings the Mystical Body of Christ to life in its midst. Cosmically, though, the divinization is categorical and assured from the start, for we belong to God and nothing can overpower the Almighty to which we belong. If we try to mastermind specifics we are out of our depth from the start, but the consensus of centuries of theological ponderings seems to be that it will occur at the end of history when time closes down and God draws his creation back into himself. He will not withdraw it into his singularity. Rather, its manifold nature will be retained with its dross transmuted into gold. There remains the question of whether ths final redemption of history is prefigured within history, and the answer is yes. An analogy and a recollection are helpful here. The analogy is the sky. Whether it is decked out in cloud-scapes, strewn with stars, or tinted a pure empyrean blue, the sky is invariably peaceful and beautiful; it can be hid by leaden rain clouds, but these do not affect the sky itself. And it is always with us. Even when it is obscured, we know that it is there. The temporal counterpart of the sky is eternity. It too is peaceful and beautiful, whereas history is anything but. And just as the sky enfolds the earth, eternity enfolds history. Both eternity and sky can take the initiative in calling themselves to our attention. Even when our minds are on other things, the sky can suffuse our experiences with sunlight or rain, and likewise eternity can break into the moments of our experience with lightning flashes of illumination. It does this most noticeably by saying no to history’s moments. We are so caught up in history that we forget that, taken as freestanding, history is unredeemable. To say that hope and history are always light-years apart is an understatement — they are incommensurate, for between finitude and the infinite there is no common measure. Periodically, eternity breaks into history to remind us that history cannot stand on its own feet. First eternity pronounces its “no” on free-standing history, and then it draws history to its bosom and enfolds it with its “yes” — smothers it in its peace and beauty. Eternity can also break into our moments of daily preoccupation like flashes of lightning on a dark night. [“Something broke and something opened./ I filled up like a new wineskin,” said writer Anne Dillard.] A friend of ours who is a therapist told us recently of how she had witnessed such an opening in her office the day before: A client had come for her weekly appointment more than usually depressed. It had been the week of her birthday and she had not heard from any of the family she had grown up in. They had become fundamentalists and thought she was damned. “My mother died last year and now I’ve lost the rest of them. It makes me sick,” she said, too tight with pain to cry. Then, after an unusually long silence, she murmured quietly as if to herself, “Something is happening to me.” Her hands, which had been clenched in angry fists, now lay open on her lap and tears were streaming down her cheeks. Then, “I’m feeling something wonderful. Something wonderful has entered the room. It just came, didn’t it?” She found herself laughing, though she tried to suppress it because it seemed inappropriate. “I’m going to take the initiative and write to them,” she said. “Shoot affectionate greetings to them like paper airplanes.” Sometimes intimations of eternity seem simply to drop from heaven into our laps, as Czeslaw Milosz registers in his poem “Gift.” A day so happy Fog lifted early. I worked in the garden. Hummingbirds were stopping over the honeysuckle flowers. There was no thing on earth I wanted to possess. I knew no one worth my envying him. Whatever evil I had suffered, I forgot. To think that once I was the same man did not embarrass me. In my body I felt no pain. When straightening up, I saw blue sea and sails. And from an anonymous poet: I am so filled with ghosts of loveliness That I could furbish out and populate a distant star, So the gods could congregate to gaze, and memorize, and duplicate. Table of Contents: 1. The Christian worldview 2. The Christian story 3. The three main branches of Christianity today Coda |

|