|

Posted

January 7, 2013

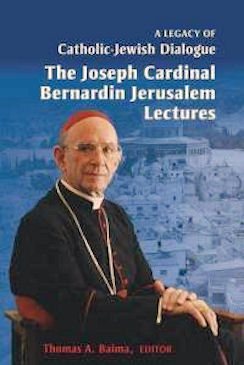

Book: A Legacy of Catholic-Jewish Dialogue: The Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Jerusalem Lectures Editor: Thomas A. Baima Liturgical Training Publications. Chicago, IL. 2012. pp. 212 An Excerpt from the Book:

An Excerpt from the Book: In what ways is the Gospel of Matthew Jewish and what can we learn from it? The narrative implies that the author of Matthew around 90 C.E. hoped to attract members of the larger Jewish community to Jesus's new interpretation of the Jewish tradition. He cites the Bible frequently, using Hebrew and Greek versions, in order to authenticate his view of Jesus and his teaching. Matthew's Jesus fits comfortably within first-century Jewish understandings of how God guides human affairs and acts through divinely empowered agents. Typological associations of Jesus with Moses, personified Wisdom, and the prophets resonate deeply with the first-century Jewish understandings of history and its heroes. The author Matthew is an informed participant in a number of first-century Jewish legal debates. Second Temple Jewish documents such as the Book of Jubilees, the Temple Scroll, and the Covenant of Damascus as well as the early strata of the Mishna, finally edited about 200 C.E., argued over tithing, the validity of oath and vows, the conditions of divorce, the exact requirements of Sabbath, the conditions of purity, and dietary laws. The Pharisee, Sadducees, and priestly factions clashed over these items before the Temple was destroyed, and their heirs continued the disputes afterwards. Matthew joins in this debate as a serious defender of his group's understanding of how one should live as a Jew according to the teachings of Jesus. He accepts the Jewish Bible and bases his arguments on it, using the types of reasoning found in first-century Jewish literature. But he sees the whole tradition through the eyes of Jesus as he understands him. Many argue that Matthew's polemics against the Jews proved that he has left the Jewish community. But his harsh attacks against his opponents and their positions are typical of inner Jewish sectarian conflict. In fact, vilification of one's rivals and opponents appears in modern political campaigns in the United States and in Israel and in ancient Jewish, Greco-Roman, and Christian literature. Bare-knuckle power struggles among rival groups go back as far as we have writing. Matthew's accusations of hypocrisy and blindness against his opponents, the "scribes and Pharasees" in chapter twenty-three, communicate the same message as the epithets "Wicked Priest," "Scoffer," "man of the Lie," and "Seeker After Smooth Things: that lace the Dead Sea Scrolls. Significantly, the author of Matthew, like the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, attacks only the leader of the Jewish community who, in his judgment, culpably rejected Jesus and misled the people away from him. He does not attack the Jewish people in general. In the gospel narrative the crowds of Jewish people remain for the author of Matthew fertile ground for sowing the teachings of Jesus concerning Judaism. In Matthew's late first-century setting he directs his polemics against rival leaders and their competing programs for understanding and living Judaism in the light of the loss of the Temple. Table of Contents: Introduction: What we have learned from 40 years of Catholic-Jewish dialogue Antisemitism: the historical legacy and challenge for Christians Jewish-Christian relations after the Holocaust: Toward post-Holocaust theological thought. Catholic-Jewish relations: a new agenda The theological significance of Israel Christian anti-Judaism: the first century speaks to the twenty-first century Bethsaida: home of the apostles and the rabbis An ancient and venerable people Medieval Christians and Jews: divergences and convergences How Jewish and Christian mystics read the bible Christian-Jewish relations in the enlightenment period Catholics, Jews, and American culture |

|