|

Posted August 25, 2005

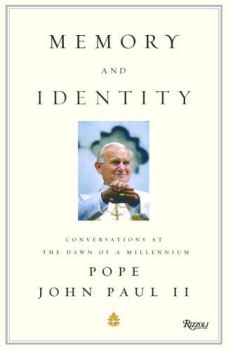

Book: Memory and Identity: Conversations at the Dawn of a Millennium Author: Pope John Paul II Rizzoli, New York, pp. 172 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

An Excerpt from the Book: Freedom is for Love Recent history has provided ample and tragically eloquent evidence of the evil use of freedom. Yet a positive answer still needs to be given to the underlying question: What does freedom consist of and what purpose does it serve? Here we are addressing a problem which, if it has always been important in the past, has become even more so since the events of 1989. What is human freedom? The answer can be traced back to Aristotle. Freedom, for Aristotle, is a property of the will which is realized through truth. It is given to man as a task to be accomplished. There is no freedom without truth. Freedom is an ethical category. Aristotle teaches this principally in his Nicomachean Ethics, constructed on the basis of rational truth. This natural ethic was adopted in its entirety by Saint Thomas in his Summa Theologiae. So it was that the Nicomachean Ethics remained a significant influence in the history of morals, having now taken on the characteristics of a Christian Thomistic ethic. Saint Thomas embraced the entire Aristotelian system of virtues. The good that is to be accomplished by human freedom is precisely the good of the virtues. Most of all, this refers to the four so-called cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance. Prudence has a guiding function. Justice regulates social order. Temperance and fortitude, on the other hand, discipline man’s inner life, that is to say, they determine the good in relation to human irascibility and concupiscence: vis irascibilis and vis conscupiscibilis. Hence, the Nicomachean Ethics are clearly based upon a genuine anthropology. The other virtues take their place within the system of the cardinal virtues, subordinated to them in different ways. This system, on which the self-realization of human freedom in truth depends can be described as exhaustive. It is not an abstract or a priori system. Aristotle sets out from the experience of the moral subject. Likewise, Saint Thomas finds his starting point in moral experience, but through this he also seeks the light that is offered by Sacred Scripture. The greatest light comes from the commandment to love God and neighbor. In this commandment, human freedom finds its most complete realization. Freedom is for love: its realization through love can even reach heroic proportions. Christ speaks of “laying down his life” for his friends, for other human beings. In the history of Christianity, many people in different ways have “laid down their lives” for their neighbor, and they have done so in order to follow the example of Christ. This is particularly true in the case of martyrs, whose testimony has accompanied Christianity from apostolic times right up to the present day. The twentieth century was the great century of Christian martyrs, and this is true both in the Catholic Church and in other Churches and ecclesial communities. Returning to Aristotle, we should add that, as well as the Nicomachean Ethics, he also left us a work on social ethics. It is entitled Politics. Here, without addressing questions concerning the concrete strategies of political life, Aristotle limits himself to defining the ethical principles on which any just political system should be based. Catholic social teaching owes much to Aristotle’s Politics and has acquired particular prominence in modern times, thanks to the issue of labor. After Leo XIII’s great encyclical, Rerum Novarum, the twentieth century saw several more magisterial documents, of vital importance for many issues that gradually surfaced in the social arena. Pius XI’s encyclical Quadragesimo anno, marking the fortieth anniversary of Rerum Novarum, directly addresses the labor issue. In Mater et Magistra, John XXIII, for his part, offers an in-depth discussion of social justice with reference to the vast sector of agricultural labor; later, in the encyclical Pacem in Terris, he sets out the ground rules for a just peace and a new international order, resuming and further exploring certain principles already contained in some important statements by Pius XII. Paul VI, in his apostolic letter Octogesima Adveniens, returns to the issue of industrial labor, while his encyclical Populorum Progressio analyzes the various elements of just development. All these issues were proposed for the reflection of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council, and they received particular attention in the constitution Gaudium et Spes. Setting out from the fundamental notion of the human person’s vocation, this conciliar document analyzes one by one the many different dimensions of this vocation. In particular, it dwells on marriage and the family, it considers cultural issues, and it addresses complex questions of economic, political, and social life both nationally and internationally. I myself returned to the last of these issues in two encyclicals, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis and Centesimus Annus. Yet earlier still, I had devoted a whole encyclical to human labor, Loborem Exercens. This document, intended to mark the ninetieth anniversary of Rerum Novarum, was published late because of the attempt on my life. At the heart of all these magisterial documents lies the theme of human freedom. Freedom is given to man by the Creator as a gift and at the same time as a task. Through freedom man is called to accept and to implement the truth regarding the good. In choosing and bringing about a genuine good in personal and family life, in the economic and political sphere, in national and international arenas, man brings about his own freedom in the truth. This allows him to escape or to overcome possible deviations recorded by history. One of these was certainly Renaissance Machiavellianism. Others include various forms of social utilitarianism, based on class (Marxism) or nationalism (national socialism, fascism). Once these two systems had fallen in Europe, the societies affected, especially in the former Soviet bloc, faced the problem of liberalism. This was treated at length in the encyclical Centesimus Annus and, from another angle, in the encyclical Veritatis Splendor. In these debates the age-old questions return, which had already been treated at the end of the nineteenth century by Leo XIII, who devoted a number of encyclicals to the issue of freedom. From this rapid outline of the history of thought on this topic, it is clear that the issue of human freedom is fundamental. Freedom is properly so called to the extent that it implements the truth regarding the good. Only then does it become a good in itself. If freedom ceases to be linked with truth and begins to make truth dependent on freedom, it sets the premises for dangerous moral consequences, which can assume incalculable dimensions. When this happens, the abuse of freedom provokes a reaction which takes the form of one totalitarian system or another. This is another form of corruption of freedom, the consequence of which we have experienced in the twentieth century, and beyond. Table of Contents:The Limit Imposed Upon Evil1. Mysterium Iniquitatis: The coexistence of good and evil. 2. Ideologies of evil 3. The limit imposed upon evil in European history 4. Redemption as the Divine limit imposed upon evil 5. The mystery of redemption 6. Redemption: victory given as a task to man Freedom and Responsibility 7. Toward a just use of freedom 8. Freedom is for love 9. The lessons of recent history 10. The mystery of mercy |

|