|

Posted September 24, 2007

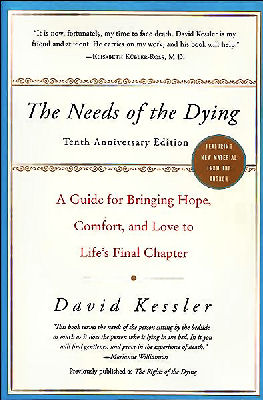

Book: The Needs of the Dying: A Guide for Bringing Hope, Comfort, and Love to Life’s Final Chapter Author: David Kessler Harper, New York. 2007. Pp. 224 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

An Excerpt from the Book: Appropriate Feelings Other people are uncomfortable when they see us in pain. They may be upset because the don’t want to see us suffer. They may be upset because we are not expressing our distress in the “proper” way. They might like us to respond to our pain politely, stoically, or with only a modest hint of discomfort in the voice to prove that the pain is real. They certainly do not want us screaming and cursing or being embarrassing or disruptive. Screaming and yelling are normal responses to pain. I’m more surprised when people don’t scream and holler when they’re in excruciating pain, but we’ve been thoroughly trained not to give voice to our “bad” feelings. Your loved ones, your doctors, and your nurses may not like how you feel your pain or how you express it, but it’s your pain and you have a right to express your feelings and emotions about it in your own way. When you’re facing a life-threatening and painful illness you may feel angry, depressed, fearful, anxious, outraged, or terrified. Whatever you feel, your feelings are correct and you are entitled to them. Even feeling nothing is proper. Joseph, a colleague of mine and a physician, once called after learning that his uncle had cancer of the lungs, bone, and pancreas. “I expected to have a huge emotional reaction,” the puzzled doctor said, “but I felt nothing. All I can do is talk to my relatives intellectually about his situation. My uncle has meant so much to me, I don’t understand why I am not feeling more.” We feel our feelings when they hit us, not when we think we should. Joseph is a very caring and compassionate man. Perhaps he was still in shock. Perhaps he would have another reaction when he visited his uncle in the hospital. Perhaps he was simply too uncomfortable with “bad” feelings to allow himself to experience them at all. I reminded Joseph of his love and compassion, telling him that he would cry when he was ready to and that the time when he finally cried would be the right time. Numbness, denial, and withdrawal are all appropriate reactions, for the moment. They will make way for other emotions at the right time but not before. Rather than sort through our feelings to find the “right” one, it’s better to simply let them wash over us in their own time. When I discussed Joseph’s case with Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, she said in her simple and profound way, “What you’re feeling is what you’re feeling. Don’t judge it, just let it be.” Elisabeth has shared with me how painful her last year was for her. She’s ready to die, but she was not dying — nor was she getting well. My place as a friend was to allow her to have her feelings, to listen and to be there for her. I brought her things to read, favorite foods, and, hopefully, some good companionship. She herself often said that if you’re still here, it is for a purpose. Feelings sometimes are overwhelming. If you are feeling as if you cannot go on because a loved one is dying, it’s okay to take a break or get help. There is a surprising amount of help available. There are support groups for people facing a life-challenging illness, for people with cancer, as well as groups for family, friends, and significant others. Many of these groups are listed in your local telephone book. You can always speak to a hospital minister, priest, rabbi, or social worker, who are excellent resources. Your doctor or therapist can also help you through your emotional stress. People at their wits’ end have often said, “I thought about taking a Xanax or something to help me calm down but decided I shouldn’t.” They say that they don’t want to take drugs for fun.” Drugs may certainly be overused, but there is an appropriate time for medicine, and dealing with death is just the time for which many medications were created. Unless you have a history of addiction, it’s all right to look for help from appropriate medications at a moment of overwhelming sorrow or anxiety. If you’re numb with shock, that’s all right. If you’re furious, if you’re outraged, if you’re sad, if you’re crazed, or if you need help, that’s all right too. All of your feelings are appropriate. Table of Contents: 1. A living human being 2. Expressing emotions 3. Participating in decisions 4. The physiology of pain 5. The emotions of pain 6. Spirituality 7. Children 8. What death looks like 9. Dying in the eye of the storm 10. Not dying alone 11. The body |

|