|

Posted July 18, 2005

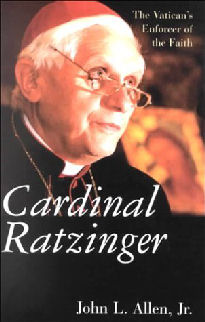

Book: Cardinal Ratzinger: The Vatican’s Enforcer of the Faith Author: John L. Allen, Jr. Continuum, New York, pp. 340 An Excerpt from the Introduction:

“I regret very much that Cardinal Ratzinger gets a bad press because I think people, due to a lot of prejudices or their own theological positions, don’t always give themselves the opportunity to really hear the man, to really hear what he’s got to say. He is a man of tremendous faith, of great integrity, very great intellect and great dedication. I just wish people would allow themselves the opportunity to listen more carefully to what he’s saying, what’s behind what he’s saying, where he’s coming from, what theology really means to him. I think if people really did that they would find that one of the big barriers slips away.” Having listened to Ratzinger himself, I think Culllinane is right. I can say without irony, and despite the incredulity of some of my colleagues, that in the unlikely event I ever had access to Ratzinger as a confessor, I would not hesitate to open my soul to him, so convinced am I of the clarity of his insight, his integrity, an his commitment to the priesthood. An Excerpt from the Book: Ratzinger’s most important ecclesiological work during this period was Das neue Volk Gottes, which appeared in 1969. In the Counter-Reformation era, he says, the emphasis was on the visible, external church; in the period after the First World War., Catholics needed a deeper spirituality and accented the invisible church. This latter stance, however, led to a “disdain: for external structures. Ratzinger quotes Augustine as a corrective: “Inasmuch as anyone loves Christ’s church, to that degree he possesses the Holy Spirit.” Ratzinger’s synthesis is a “communion ecclesiology,” arguing that the church is a mystical communion of local communities, not in the sense of a political federation, but rather a sacramental bond. It is both visible and spiritual, exterior and interior. The communion unites God and man, visible and invisible dimensions of the church, hierarchy and flock, local and universal churches. As prefect, Ratzinger would insist that fostering communion ecclesiology was the chief aim of Vatican II. Like most big ideas, communion ecclesiology is interpreted in different ways. For progressives, calling the church a communion means it is not a monarchy or a corporation. Instead of orders being handed down from on high, decisions should reflect the sense of the community. For conservatives, calling the church a communion means it is not a democracy. Instead of determining policy by votes and pressure politics, the church operates on the basis of trust and submission to authority. Dissent has logic in a state formed by social contract, but not in a communion, where parties and factions are out of place. One measure of the shift in Ratzinger is that his earlier writings lean toward the first way of understanding the concept, his later work toward the second. An important point for Ratzinger is that those horizontal bonds are “diachronic,” meaning they include not just the members of the church alive today but all those who have ever been part of the communion of saints. It is in this sense that Ratzinger says that one cannot ascertain the sensus fidelium, or “sense of the faithful,” merely by taking into view what a majority of Catholics thinks today. One must consider what the testimony of the church has been throughout the ages. A sacramental understanding of the church also puts a premium on the center, the papacy, as the “sign” of communion. Ratzinger writes. It is the papacy that both symbolizes and effects the bonds that tie Catholics together. In Das neue Volk Gottes Ratzinger returns to his mentor St. Bonaventure, in part to warn against taking this exalted view of the papacy to an extreme. Bonaventure’s own view of the role of pope was forged in the controversies of the thirteenth century, when the mendicant orders had come under fierce attack from many “traditionalists.” (Franciscans and Dominicans lived and worked not in monasteries or parishes but in the world, sustained by begging – hence “mendicant”) The Franciscans looked to a strong, assertive papacy to defend them. Bonaventure thus developed a view of the papacy that today can only seem alarmingly exalted. He argued that the pope is the “criterion” or “ideal” of humanity, that the pope has the same role in the New Testament economy of salvation as the Jewish high priest had in the Old, and that the pope acts as head of the body of Christ. Ratzinger dismisses this as overblown rhetoric, suggesting the need for a “spirit of moderation and the just mean.” Table of Contents: 1. Growing up in Hitler’s shadow 2. An erstwhile liberal 3. All roads lead to Rome 4. Authentic liberation 5. Cultural warrior 6. Holy wars 7. The enforcer 8. Ratzinger and the next conclave Works by Joseph Ratzinger |

|