|

Posted September 21, 2011

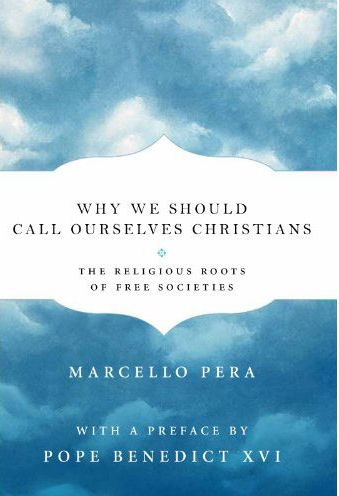

Book: Why We Should Call Ourselves Christians: The Religious Roots of Free Society Author: Marcello Pera Encounter Books. New York. 2011. Pp. 220 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

In Why We Should Call Ourselves Christians, Marcello Pera reveals that not only is this wrong, it is also dangerous. The very ideas on which liberal societies are based and in terms of which they can be justified — the concept of the dignity of the human person, the moral priority of the individual, the view that man is a “crooked timber” inclined to prevarication, the limited confidence in the power of the state to render him virtuous — are typical Christian, or, more precisely, Judeo-Christian ideas. Take them away and the open society will collapse. Anti-Christian secularism jeopardizes the identity of the West, leaving it with no conscience. The Founding Fathers of America, as well as major intellectual European figures such as Locke, Kant, and Tocqueville, knew how much our civilization depends on Christianity. “The challenge of our particular historical moment,” as Pope Benedict XVI calls them in the Preface of the book, can be faced only if we stress the historical and conceptual link between Christianity and a free society. An Excerpt from the Book: Multiculturalism What about multiculturalism, which is a political application of relativism today? Here too we must start with a well-established fact: modern societies are composed of minorities, communities, varied ethnic and cultural groups. Here too we find the same challenge: how to bind them together and govern them. Should we reduce ths complexity to a unit and oblige everyone to respect a minimum code of values, or should we give free rein to diversities and let groups govern themselves? Should we affirm that there are criteria with which we may determine whether one culture is better or worse than another, or should we assert that no common measure exists and therefore all forms of culture are to be respected by all other cultures? Liberals take the former position; relativists the latter. Multiculturalism is the political doctrine and policy deriving from this second line of thinking. But it too is indefensible for both theorectical and practical reasons. The theoretical reasons. Multiculturalism has two strong points, consisting of two arguments. The first is empirical: cultures confer identity upon individuals by giving them personality, a role, and self-awareness. One theorist of multiculturalism has written: “Culture shapes [men] in countless ways, forms them into certain kinds of persons, and cultivates certain attachments, affections, moral and psychological dispositions, taboos and modes of reasoning. Far from being purely formal and culturally neutral, their capacity for autonomy is structured in a particular way, functions within flexible but determinate limits and defines and assesses options in certain ways.” Therefore cultures are indispensable. The second argument for multiculturalism is normative. As a liberal scholar leaning toward multiculturalism has noted, a good life requires that two preconditions be satisfied: “to lead our life from the inside, in accordance to our beliefs about what gives value to life,” and “to be free to question those beliefs, to examine them in light of whatever information, examples, arguments our culture can provide.” The free society is one that not only “allows people to pursue their current way of life but also gives them access to information about other ways of life.” Therefore, “cultures are valuable not in and of themselves, but because it is only by having access to a societal culture that people have access to a range of meaningful options.” Thus, cultures are the bricks and mortar of freedom, and in order to protect this good, we must recognize the rights of cultures, which means the rights of groups. Table of Contents: Introduction When our house catches fire 1. Liberalism, the secular equation, and the question of Christianity 2. Europe, Christianity and the question of identity 3. Relativism, fundamentalism and the question of moralss |

|