|

Posted April 26, 2005

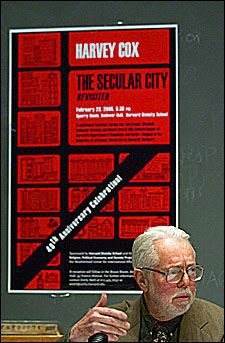

An Old Book Needed For The New Problem Of Societal Secularization Book: The Secular City Author: Harvey Cox Macmillan Company, New York, pp.244 An Excerpt from the Introduction:

To someBonhoeffer’s words still sound shocking, but they really should not. He was merely venturing a tardy theological interpretation of what had already been noticed by poets and novelists, sociologists and philosophers for decades. The era of the secular city is not one of anticlericalism or feverish antireligious fanaticism. The anti-Christian zealot is something of an anachronism today, a fact which explains why Bertrand Russell’s books often seem quaint rather than daring and why the antireligious propaganda of the Communists sometimes appears intent on dispelling belief in a “God out there” who has long been laid to rest. The forces of secularization have no serious interest in persecuting religion. Secularization simply bypasses and undercuts religion and goes on to other things. It has relativized religious world views and thus rendered them innocuous. Religion has been privatized. It has been accepted as the peculiar prerogative and point of view of a particular person or group. Secularization has accomplished what fire and chain could not: It has convinced the believer that he could be wrong, and persuaded the devotee that there are more important things than dying for the faith. The gods of traditional religions live on as private fetishes or the patrons of congenial groups, but they play no significant role in the public life of the secular metropolis. An Excerpt from the Book: The Styles of the Secular City Technopolis, like the civilization it displaces, has its own characteristic style. The word style here refers to the way a society projects its own self-image, how it organizes the values and meanings by which it lives. The secular-urban style springs in part from the societal shape provided by the anonymity and mobility we have just discussed. But it is not merely a product of these factors. The style has a life of its own which in turn influences and alters the shape on which it is based. Style and shape affect each other. Both comprise that configurational whole which we have called the maniere d’etre of the secular city. Two motifs in particular characterize the style of the secular city. We call them pragmatism and profanity. We use these words at some risk of confusion, since for many people pragmatism refers to a particular movement in American philosophy and profanity simply means obscene language. Both these usages are derivative, however, and our intention here is to call to mind their original meaning. By pragmatism we mean secular man’s concern with the question “Will it work?” Secular man does not occupy himself much with mysteries. He is little interested in anything that seems resistant to the application of human energy and intelligence. He judges ideas as the dictionary suggests in its definition of pragmatism by the “results they will achieve in practice.” The world is viewed not as a unified metaphysical system but as a series of problems and projects. By profanity we refer to secular man’s wholly terrestrial horizon, the disappearance of any supramundane reality defining life. Pro-fane means literally “outside the temple” — thus “having to do with this world.” By calling him profane, we do not suggest that secular man is sacrilegious, but that he is unreligious. He views the world not in terms of some other world but in terms of itself. He feels that any meaning he finds must be found in this world itself. Profane man is simply this-worldly. To make even clearer what we mean by pragmatism and profanity, two characteristically twentieth-century men will be introduced as personifications of these elements of the secular style. The late American President John F. Kennedy embodies the spirit of the pragmatic; Albert Camus, the late French novelist and playwright, illustrates what we mean by this-worldly profanity. . . . If we do accept man as pragmatic and profane, we seem to sabotage the cornerstone of the whole theological edifice. If secular man is no longer interested in the ultimate mystery of life but in the “pragmatic” solution of particular problems, how can anyone talk to him meaningfully about God? If he discards suprahistorical meanings and looks in his “profanity” to human history itself as the source of purpose and value, how can he comprehend any religious claim at all? Should not theologians first divest modern man of his pragmatism and his profanity, teach him once again to ask and to wonder, and then come to him with the Truth from Beyond? No. Any effort to desecularize and deurbanize modern man, to rid him of his pragmatism and his profanity, is seriously mistaken. It wrongly presupposes that a man must first become “religious” before he can hear the Gospel. It was Dietrich Bonhoeffer who firmly rejected this erroneous assumption and pointed out that it bore a striking parallel to the long-discarded idea that one had to be circumcised a Jew before becoming a Christian. Bonhoeffer insists that we must find a nonreligious interpretation of the Gospel for secular man. He is right. Pragmatism and profanity, like anonymity and mobility, are not obstacles but avenues of access to modern man. His very pragmatism and profanity enable urban man to discern certain elements of the Gospel which were hidden from his more religious forebears. John F. Kennedy and Pragmatism Urban-secular man is pragmatic. In the dictionary sense of the word, this means he concerns himself with “practical or material affairs” and is interested in the “actual working out of an idea in experience.” He devotes himself to tackling specific problems and is interested in what will work to get something done. He has little interest in what have been termed “borderline questions: or metaphysical considerations. Because religion has concerned itself so largely precisely with these things, he does not ask “religious” questions. The preceding paragraph could very well serve as a thumbnail sketch of the political style of John F. Kennedy. Once at a dinner party, a guest seated next to Walt W. Rostow, at the time planning director for the State Department, asked him what President Kennedy was “really life.” After some hesitation Rostow replied, “Well, I would use one word to characterize him. He is a pragmatist.” Though cryptic, Rostow’s answer was actually exceedingly apt. Mr. Kennedy represented just that no-nonsense practicality and interest in workable solutions that is best characterized by the word pragmatism. . . . The Gospel does not call man to return to a previous stage of his development. It does not summon man back to dependency, awe, and religiousness. Rather it is a call to imaginative urbanity and mature secularity. It is not a call to man to abandon his interest in the problems of this world, but an invitation to accept the full weight of this world’s problems as the gift of its Maker. It is a call to be a man of this technical age, with all that means, seeking to make it a human habitation for all who live within it. Table of Contents:Introduction: The Epoch of the Secular CityPart One: The Coming of the Secular City 1. The Biblical Sources of Secularization 2. The Shape of the Secular City 3. The Style of the Secular City 4. The Secular City in Cross-Cultural Perspective Part Two: The Church in the Secular City 5. Toward a Theology of Social Change 6. The Church as God’s Avant-gard 7. The Church as Cultural Exorcist Part Three: Excursions in Urban Exorcism 8. Work and Play in the Secular city 9. Sex and Secularization 10. The Church and the Secular University Part Four: God and the Secular Man 11. To Speak in a Secular Fashion to God |

|