|

Posted May 29, 2011

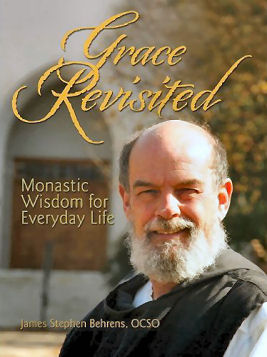

Book: Grace Revisited: Epiphanies from a Trappist Monk Author: James Stephen Behrens, OCSO Acta Publications, Chicago, IL. 2011. Pp. 220 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

An Excerpt from the Book: Christopher Street The memory is simple and returns to me often and unbidden. It is a delight when it comes and lingers for a while. It seems to like, as I do, the quiet of the woods here at the monastery, for that is where it comes to me with such ease. The memory is of my mom and dad, sitting in their bedroom before going to bed on a warm summer night. We had a large old home on Christopher Street in Montclair, New Jersey. It was a Dutch colonial, and their bedroom was on the second floor. The rest of us, five sons and two daughters and my grandmother — Dad’s mom — were scattered comfortably throughout the rest of the house. Jimmy, my twin, and I slept in a small room on the third floor, which had two closets — as if it was made just for twins. We had our own bathroom at the end of a long hall, and there was a large porcelain tub in thre with legs shaped like lion’s feet. The toilet was right next to the window that overlooked the back yard, and from that window the Manhattan skyline was visible. Before going to bed, each of us would stop in and say goodnight to Mom and Dad. We would sit on their bed and chat for a little while. Gram used to stick her head in the door and say a soft goodnight. Dad sat in a large maroon-colored chair by the front window, and Mom sat on the other side of the same window, at Dad’s desk. They wore pajamas, and if the night was chilly they wore robes. Mom wore a simple blue robe; Dad’s was maroon — the same color as his chair. They smoked back then, though I do not remember the room smelling all that strongly of cigarettes. There was a stronger, sweet smell of talc or perfume. They always had a nightcap before going to bed, usually a light scotch with water. On summer nights, their window was open unless there was a heavy rain. We could hear cars passing by as we spoke, as well as the occasional soft tread or slap of someone’s feet as he or she passed in front of the house. Air conditioning was not common back then, and on a hot summer’s night people would take walks in the evening to cool off a bit. I can see the scene above perfectly, almost fifty years later. With a little effort, I can hear my parents’ voices and observe their younger faces. I remember the desk and the ashtray, the pens and the yellow legal pads, an old adding machine. There are a few magazines on the cream-colored radiator cover in front of the window. Mom’s and Dad’s slippers are under their bed. The lace curtain moves just a bit, toyed with by a light summer breeze. There are lights on in the houses across the street, partially obscured by the large trees that were and I hope still are one of the real treasures of Christopher Street. There is a single street lamp, burning bright and around which hundreds of moths swirl and swirl. Dat sits with his legs crossed — “man style,” and Mom sits in her chair which is pulled away from the desk and facing me. Her legs are crossed, too, but “ladylike.” Her hair is dark, though thre are wisps of gray. She keeps it in place with bobby pins. There are separate dressers on either side of the door. My brothers, Robert and Peter, are long asleep in a room to the left. I can almost touch and feel the things I see: Mom’s silver-platted hair brush and mirror set, her jewelry, the little statue of a woman with a fine china dress, stacks of letters and coupons, a few broken rosaries. On Dad’s bureau are some papers, a pair of black socks, a shoe horn, his wallet, an open pack of cigarettes, and his Zippo lighter. They smoked non-filtered Pall Malls. Mom would always get a tiny bit of tobacco on her lip when she would take a drag on her cigarette. I can see the exact way her hand would go to her lips and gently remove the little piece. I picture myself in that room, watching them, listening to them, saying a goodnight and kissing them and then heading on upstairs to bed. I can remember the soft cheek of my mom and the sweet smell of Pont’s cold cream as I kissed her. I remember the stubble on Dad’s cheek as I kissed him and the faded but still unmistable smell of the Mennen’s Skin Bacer he had splashed on his freshly shaven face that morning. What did we speak of those many nights? I cannot recall a single conversation in detail. The words escape me, but the sensual memory is strong: the smells, the sights, the colors, the breeze, the distant sound of footsteps of a long gone night walker. The memory has lasted and seems to grow stronger with each passing year, especially since my dad died a few years ago. It is strange, even wondrous, when you think about it! We humans are constantly trying to imagine what God is like. Is the divinity male or female, near or far, all knowing, all powerful? We Christians believe that men and women are created in the image and likeness of God. So perhaps learning about God is coextensive with learning about ourselves: how we become who we are, how we remember, and what we remember. We think of God as some sort of grandiose finished being, and yet our lives, if they are truly human lives at all, become so only through encounters that come scented with Mennen’s Skin Bracer and Pond’s Cold Cream. God’s incarnate love comes to me carried by the still warm breezes of past summer nights, nights when Mom and Dad mysteriously did the “God thing” by living their vows and letting the awesome power of their love seep into and lay claim to the ordinariness of their lives. Any one of those nights were like so much leaven, working its magic over the years, stubbornly refusing to be remembered as “inconsequential.” Table of Contents: Part 1 Grace is Everywhere Interlude Andy’s Diner Part 2 Memories of Grace |

|