|

Posted April 19, 2006

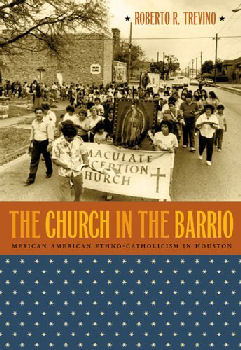

Book: The Church in the Barrio: Mexican American Ethno-Catholicism in Houston Author: Roberto R. Trevino The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2006, pp. 308 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

Houston’s native-born and immigrant Mexicans alike found solidarity and sustenance in their Catholicism, a distinctive style that evolved from the blending of the religious sensibilities and practices of Spanish Christians and New World indigenous peoples. Employing church records, newspapers, family letters, mementos, and oral histories, Trevino reconstructs the history of several predominately Mexican American parishes in Houston. He explores Mexican American Catholic life from the most private and mundane, such as home altar worship and everyday speech and behavior, to the most public and dramatic, such as neighborhood processions and civil rights protest marches. He demonstrates how Mexican Americans’ religious faith helped to mold and preserve their identity, structured family and community relationships and institutions, provided both spiritual and material sustenance, and girded their long quest for social justice. An Excerpt from the Book: Legitimation or Control? The Encuentros The activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s culminated in an institutional response by the hierarchy of the U.S. Catholic Church called an encuentro, a meeting to address problems. Father Edgard Beltran, an activist priest from Latin America, suggested the idea in the fall of 1971 while visiting the Archdiocese of New York. The idea soon gained support in the U.S. hierarchy and thus the first Encuentro Hispano de Pastoral (Pastoral Congress for Spanish-Speaking) became a reality in June 1972. For the first time, the Catholic Church in the United States provided a national forum for leaders of Spanish-speaking communities throughout the nation to air their grievances. Two hundred and fifty delegates met in Washington, D.C., to examine the place of the Spanish-speaking in the church. “It was a meeting,” said Bishop Patricio Flores, “called by the Church not to praise, but to make a self-evaluation and correct what is wrong. “What was “wrong”, essentially, was that Mexican-origin and other Spanish-speaking peoples – 25 percent of the U.S. Catholic population – had virtually no voice in the institutional church and were not adequately served by it, pastorally or socially. Adequate representation was the central theme of the national encuentro: “If we are 25 percent of the church, we should participate in 25 percent of . . .the committees of the national church,: Bishop Flores demanded. The three-day meeting produced seventy-eight conclusions and demands calling for “greater participation of the Spanish-speaking in leadership and decision-making roles at all levels within the American Church.” The crescendo of Chicano demands struck a responsive chord within the U.S. Catholic Church. On the national level, for instance, the church responded by naming more Mexican American bishops. . . . But others were less optimistic. Had the church co-opted the Chicano movement, channeling protest into a controlled environment of its own creation? At the Houston regional encuentro, poet Lalo Delgado extemporaneously harangued attendees for seventy minutes about the long-standing neglect of Mexicans by the Catholic Church in the United States and the festering discord many Chicanas and Chicanos felt toward the institution. At the same meeting, national lay leader Pablo Sedillo hinted at co-optation, reminding listners taht similar meetings had taken place before, with nearly identical conclusions, yet nothing had changed. Sedillo voiced what many Mexican Catholics had experienced historically: “To date there has been a commitment of words, lip service, but no real action.” Ultimately Sedillo offered a cautiously optimistic assessment of the encuentro and the juncture Mexican Catholics and the institutional church had reached. Table of Contents: 1. Tejano Catholicism and Houston’s Mexican American community 2. Ethno-Catholicism: empowerment and way of life 3. The poor Mexican: church perceptions of Texas Mexicans 4. Answering the call of the people: patterns of institutional growth 5. In their own way: parish funding and ethnic identity 6. The Church in the Barrio: the evolution of Catholic Social Action 7. Faith and justice: the church and the Chicano Movement |

|