|

Posted November 5, 2004

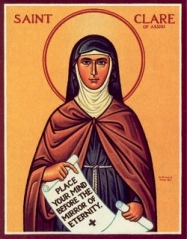

Book: An Unencumbered Heart: A Tribute to Clare of Assisi 1253 - 2003 From: Spirit and Life: A Journal of Contemporary Francisanism St. Bonaventure University, NY, pp.76 An Excerpt from the Introduction:

Although that simple desire seems all but natural in a self-proclaimed Christian society like the one she belonged to, Clare really had to struggle to have her evangelical way of life acknowledged, much less understood. Was living according to the Gospel taken for granted in medieval Christianity? Maybe, but maybe it is why the Church’s leaders of the time had more than one problem with Clare’s radicalism and seriousness of purpose. Clare was determined. She knew what she wanted, and nobody - be he pope, cardinal, or visitator - would change her wonderful mind. “Hold what you are holding, do what you are doing, and do not cease,” she wrote to her friend and soul mate in distant Prague, Princess Agnes. It took Clare her life time to obtain the recognition she wanted: the papal written approval of the life of the Poor Sisters in San Damiano. When finally on 9 August 1253 she got the long awaited bull, she had done what she had to do. Two days later, she passed from time into eternity. Seven hundred and fifty years later, 2003 was the year of many celebrations around the world in honor of Clare of Assisi. In tribute Franciscan Institute Publications decided to dedicate another volume of the Spirit and Life series to the first Franciscan woman. Here it is, “An Unencumbered Heart” The Tribute to Clare of Assisi. An Excerpt from the Journal: The social logic of the texts of Clare’s Letters to Agnes of Prague establish that the four Letters reveal Clare’s influence among her own sisters and brothers, both locally and in regions far beyond San Damiano. Concretely, Clare’s Letters were written amidst serious problems – hunger and illness among her sisters in San Damiano monastery, the threat of invasion from warring nobles and merchants in the Umbrian valley and protracted controversies with papal and episcopal authorities on issues related to women’s autonomy and service among the poor. However, all of the writings attributed to Clare’s authorship — the Form of Life, the four Letters to Agnes of Prague, the Testament and the Blessing – like any authored works, potentially contain within them ideologies that internally contradict themselves. Spiegel reminded us that, “all texts occupy determinant social spaces, both as products of the social world of the authors and as textual agents at work in that world, with which they entertain often complex and contestatory relations.” The relations established in Clare’s writings in general, and in her Letters to Agnes in particular, are associated with poverty, chastity and obedience, descriptions of traditional evangelical counsels or vows. Clare’s very descriptions embody inter-textual contradictions. For her, poverty comprised a commitment to give up earthly wealth for heavenly riches. Chastity involved giving up the right to take an earthly spouse with the promise of gaining a heavenly one. Obedience, whether to the abbess or to a Church official, meant forfeiting secular domination or patronage only to be dominated by ecclesial power . . . . Clare’s Letters gave voice and witness to her method and its effectiveness. In particular, she herself mirrored the way of prayer she taught: gaze, consider and contemplate in order to become, not only imitate, the love of God incarnated in the poor Crucified Jesus. Fidelity to such prayer as a way of life enabled her to remain steadfast in the ideal of poverty, to sustain relationships between the Poor Ladies and the Brothers and the papacy, and to establish a legacy available to women who would follow in her footprints. The following did not involve merely imitating the sufferings of Jesus who was himself the victim of religious and political tensions of his day. No, this was not a spirituality of mere self-sacrifice but one of self-gift. Such following actually involved the identification with Jesus who came as a poor child and lived without religious or social status. In other words, there was no denying that fact that through the incarnation of Jesus, God chose to come among humans as poor and identified with them in their daily plight. It was truly an incarnation of Love, not victimization. This epitomized the manner of love that is willing to undergo suffering and debasement for the sake of the beloved, in this case, the beloved poor, who, in turn become both the mirror and the incarnation of that same love. Table of Contents: Jean Francois Godet-Calogeras Structure of Form of Life of Clare Lezlie Knox Clare of Assisi: Foundress of an Order? Jacque Dalarun Clare and Men Pacelli Millane, O.S.C. Privilege of Poverty of 1228: Rooted in the Canticles of Canticles Eileen Flanagan Medieval Epistolary Genre and the Letters to Agnes of Prague |

|