|

Posted June 3, 2009

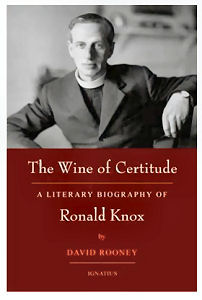

Book: The Wine of Certitude: A Literary Biography of Ronald Knox Author: David Rooney Ignatius Press. San Francisco, CA. 2009. Pp. 427 An Excerpt from the Jacket:

Rooney examines the full range of Knox’ writings including apologetics, detective fiction, satire, novels and other genres and offers an intellectual portrait that is both fascinating and engaging. The author includes many samples of Knox’s own writings throughout the book. Rooney thus uses a mosaic approach that makes the works and the person of Knox emerge from the pages in a vivid and lively way. Knox was a prolific author who wrote over seventy-five books, as well as many articles and homilies. He utilized many genres including satire, novels, spirituality, and detective stories. His literary works include The Hidden Stream, The Belief of Catholics, Captive Flames, Pastoral and Occasional Sermons and many more. With the “Knox revival” going on today and the renewed interest in his writings, as evidenced by the large Ronald Knox Society of North America, this book provides a timely and valuable addition. An Excerpt from the Book: Dealing with sin Knox is well aware that achieving this state of spiritual equanimity is no easy feat, because fallen nature inclines people to so many shortcomings and vices that impede their progress. His retreat talks are replete with shrewd insights into the more common vices dragging us down and recommendations for overcoming them, recommendations the surface simplicity of which belies a profound understanding of human psychology. “When we do try to look at our sins cooly, honestly, and see them as they are, what gets us down sometimes is not the greatness of them so much as the littleness of them; they are so paltry, so mean. We aren’t the sort of rollicking medieval Christian who killed a man and than went off on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and spent the rest of his life in sackcloth and ashes. We seem to pass our time like coral-insects, laboriously building up for themselves a great mountain of purgatory out of tiny little peccadilloes; a harsh word here, an uncharitable criticism there, petty dishonesties, almost imperceptible self-indulgence. It humiliates us somehow, to feel that we are such mediocre people, even about our sins. It’s not, of course, that we would to be more sinful than we are; only we have the feeling we might repent better if we had more to repent of. ‘Though your sins be as scarlet,’ Isaias says, ‘they shall be white as snow — yes, that is splendid; but what is ever going to rid us of this prevailing tinge of pink?” In A Retreat for Priests, the only volume of talks that were actually given on a single occasion, Knox ties in each meditation with an Old Testament personage or event. The flight from Egyptian bondage is a suitable type of the Christian’s renunciation of allegiance to the world. But the weakness shown by the Israelites mirrors our attachment to sin: “You could not but carry away with you, something of the world you had left behind. Just a keepsake, just a souvenir, of the world you had left behind. There was someone passion or some curiosity still unmortified, there was some ambitious spirit still unconquered, there was some dependence on worldly comforts or consolations, which still went with you; you found room for it, at the last moment, in your knapsack. That keepsake, that souvenir, is your danger; will grow up into a golden calf if you are not on your guard about it.” Knox devotes a whole mediation to the corrosive trait of murmuring, which betrays a lack of gratitude to God by finding fault with one’s circumstances rather than accepting them and inflicts damage on others’ reputations. How much better we would be if we could turn those occasions when we would like nothing better than to carp about someone’s shortcomings into occasions to exercise patience with fellow creatures. After all, are we really better than the people we so glibly criticize? “Most of us have some unlovable qualities which we can’t help; most of us do and say the wrong thing, without meaning to; and besides that, there are our faults. Part of the reason why God put you into the world was to exercise the patience of others by your defects; think of that sometimes when you are going to bed. It is a salutary thought . . .Your bad temper, your excessive cheerfulness, your tiresomeness in conversation; he chose the right person, didn’t he? Well, if other people are being so admirably exercised in patience by you, it seems a pity you shouldn’t be exercised by them now and again in your turn; that’s only fair. The offering of patience which you can make to God; the little things you have to put up with — and that offering is to be made in silence. How it spoils that offering if you make any comment on it in the presence of other people! You must offer it to him like a casket of myrrh, not wasting the scent by opening the lid before it gets to him.” To curb an allied sin, that of quarreling, Knox advises his hearers to imagine themselves a third party to the intemperate words they intend to use to someone’s face; that onlooker views such a display of anger with acute embarrassment. That should impress on anyone tempted to use vitriolic language that verbal assaults are not a very effective way of resolving disputes. This attention to repairing faults ought not to render us paralyzed at the magnitude of the task, as if God were demanding the impossible for us. “We mustn’t conceive the mount of the beatitudes as if it were a new Sinai, covered all over with notice-boards, only more of them. Sinai, I mean saying, ‘Thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not covet,’ and then a whole fresh lot of boards put up saying, ‘Thou shalt not be angry,’ ‘Thou shalt not call people Raca,’ ‘Thou shalt not say thou fool,’ Our Lord did say that his yoke was easy, that his burden was light, and he means it. So that when he says, ‘Your justice must give fuller measure than the justice of the scribes and Pharisees’ the point is not that we should feel bound do do a whole lot of things the scribes and Pharisees didn’t. The point is that we should go about the business of living as God wants us to live in a spirit which the scribes and the Pharisees never dreamed of.” Table of Contents: 1. A priestly life 2. The journey home 3. Tracts for the twenties 4. The body in the trunk 5. Parodies gained 6. A guide for the perplexer 7. A.L. to R.A.K. 8. The water of conviction 9. Odds and ends and Armageddon 10. Heart-religion 11. The timeless word 12. Sermons and retreats: no man but Jesus only |

|